Discussion paper

March 2022

Summary

The exercise of executive emergency powers around Australia, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, has provided impetus to examine the robustness of the parliamentary procedures that exist in order to promote scrutiny and accountability of the executive.

In Victoria, the ability of the Parliament to perform its scrutiny function is diminished by:

- the Government Business Program;

- the heavily circumscribed opportunities that exist for general, non-government business;

- the rules relating to the composition of joint investigatory committees; and

- the ability of the executive to avoid scrutiny by failing to comply with procedural requirements, of which the rules relating to orders for production of documents provide an example.These deficiencies gravely impair the ability of the Parliament to perform its constitutional role, and should be addressed as a matter of priority.

Government Business Program

Since 1993, the Legislative Assembly has set a government business program for each sitting week; when the time falls for completion of the program (normally on Thursdays at 5pm), debate is interrupted and members are asked to vote on outstanding matters set out in the program.1 Where any amendments have been made to Bills, members vote only on government amendments.

This routine circumscription of debate is undesirable.

General non-government business

The only real opportunities that exist for dealing with non-government business in the Victorian Parliament are the grievance debate under Standing Order 38, matters of public importance under Standing Order 39, the statements by members mechanism permitted under Standing Order 40, and the statements on parliamentary committee reports mechanism under Standing Order 41. It must be noted, however, that the available time permitted for these mechanisms is shared between government and non- government members.

Under Standing Order 38, a maximum of two hours is permitted for grievance debates on the first sitting Wednesday of each calendar year and every subsequent third sitting Wednesday.2

Under Standing Order 39, matters of public importance are given precedence each sitting Wednesday that is not a grievance day (or a Wednesday falling in the first sitting week of a new Parliament or session). While any member can propose a matter of public importance to the Speaker, in considering which proposals to allow the Speaker must alternate between government and non-government proposals, and allow non- government proposals “on a pro-rata basis according to the non-government representation in the House”. Only one matter of public importance can be discussed on any sitting day, and the discussion cannot last longer than two hours.

Under Standing Order 40, at the conclusion of formal business each sitting day, members are able to make 90-second statements on any topic for a maximum period of 30 minutes. Standing Order 40(2) specifies that the call is to be allocated ‘according to party/individual representation in the House’.

Under Standing Order 41, on each sitting Wednesday members are able to make statements on parliamentary committee reports (other than certain reports of the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee). The call is alternated between government and non-government members, and each member can speak for a maximum of 5 minutes.

While general business is listed in the order of business under Standing Order 36, and supposed to take place from Tuesdays to Fridays after the conclusion of government business, in reality government business consumes so much time that general business is precluded (under Standing Order 34, government business takes precedence over all other business except in relation to certain matters including the grievance debate, matters of public importance, statements by members and statements on parliamentary committee reports).

The absence of an opportunity to discuss general non-government business is a grave deficiency of the Legislative Assembly’s Standing Orders.

Joint investigatory committees: composition rules

Under the Parliamentary Committees Act 2003 (Vic), important oversight functions are conferred on joint investigatory committees of the Victorian Parliament. The composition of these committees is critically important to their ability to fulfil their functions.

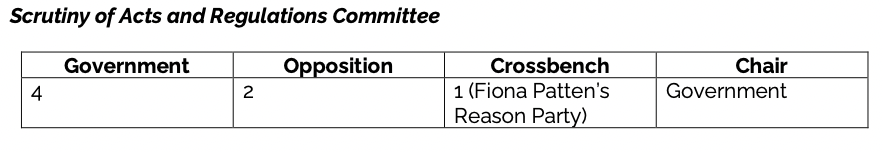

The current membership of the Victorian Parliament’s joint investigatory committees is set out below:

Currently, the only joint investigatory Committee of the Victorian Parliament which is not chaired by the Government is the Pandemic Declaration Accountability and Oversight Committee. The fact that that Committee is chaired by a non-government member is a consequence of amendments made to the Parliamentary Committees Act 2003 (Vic) as part of the negotiations to pass the Public Health and Wellbeing Amendment (Pandemic Management) Bill 2021. Pursuant to those amendments, subsection 22(1A) of the Parliamentary Committees Act provides that “The chairperson of the Pandemic Declaration Accountability and Oversight Committee must not be a member of a political party forming the Government”. Otherwise, election of committee chairpersons is governed by subsection 22(1), which simply stipulates that joint investigatory committees must elect a member as chairperson. Victoria’s joint investigatory committees would undoubtedly be more robust if subsection 22(1A) were to apply to the appointment of all chairpersons.

The same amendments also ensure that no more than half of the members of the Pandemic Declaration Accountability and Oversight Committee can be drawn from the a party forming the Government: s 21A(5) of the Parliamentary Committees Act 2003 (Cth). This too is a provision whose application should be extended to all joint investigatory committees.

The weakness of Victoria’s parliamentary scrutiny system was exposed by the COVID-19 response throughout 2020 and 2021. Up until 22 December 2020, when the Government amended the Subordinate Legislation (Legislative Instruments) Regulations 2011, there was a compelling argument that the state’s public health directions constituted legislative instruments for the purposes of the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 (Vic), and should therefore enliven that Act’s scrutiny provisions (including the jurisdiction of the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee).

However, the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee in its review of the Public Health and Wellbeing Amendment (State of Emergency Extension and Other Matters) Act 2020 (Vic) explained that it had not undertaken any review of public health directions as they not been laid before Parliament, and therefore the Committee’s powers to review the instruments under s 25A(1)(c) of the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 (Vic) (SLA) had not been enlivened.

In respect of whether directions under the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 (Vic) were legislative instruments, the Committee stated:

The Committee expresses no view as to whether the Directions ultimately may be characterised as either legislative or administrative instruments. Ultimately, ‘responsibility for decisions about statutory rules and legislative instruments lies with the responsible Minister’.3

This experience laid bare the potential for the enlivening of the SLA’s provisions to be avoided by government failure to comply with procedural requirements (although we note for completeness that such a failure to comply can be reported upon by the SARC to the Parliament under s 16B(3) of the SLA): the dependence of the SARC’s jurisdiction on such compliance is a real weakness of the scrutiny scheme that should be urgently remedied. For example, as a consequence of amendments made to the Public Health and Wellbeing Amendment (Pandemic Management) Bill 2021, the jurisdiction of the Pandemic Declaration Accountability and Oversight Committee is not expressed to be dependent upon government compliance with any matter (s 165AS of the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 (Vic)).

Avoiding scrutiny: rules relating to orders for the production of documents

Under Standing Order 11.01 of the Legislative Council, the Council may order the tabling of documents; Standing Order 11.03 enables the government to claim executive privilege in response to such a request.

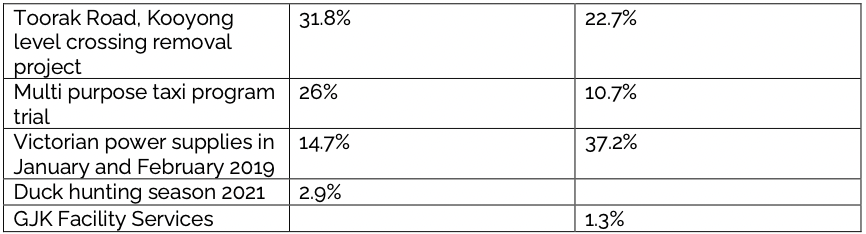

Table 1 sets out cases where the Government has claimed executive privilege in full or in part, in relation to documents it has identified as relevant as part of responding to an order for production made by the Legislative Council in the course of the 59th Parliament

Pursuant to Standing Orders 11.04 and 11.05, where there arises a dispute in relation to a claim of executive privilege, an independent arbiter can be appointed to determine the claim. However, the involvement of such an arbiter depends upon executive compliance with the requirement of Standing Order 11.03(1) to provide to the Clerk documents in relation to which privilege is claimed. Because no Victorian government has ever complied with this requirement, the independent arbiter provision has never been able to be used. It is difficult to see how this practice can be characterised as anything other than an effort to avoid scrutiny mechanisms: in effect, as the Clerk of the Victorian Legislative Council has observed, this practice means that “the Government regards itself as the sole arbiter of its own claim”. 4

Download a PDF of this paper

References:

2 Different provision is made for the first sitting week of a new Parliament or session.

3 Alert Digest No 8 of 2020 (September 2020) p 26.

4 Andrew Young, submission to the Tasmanian Legislative Council Select Committee on the Production of Documents, https://www.parliament.tas.gov.au/ctee/Council/Submissions/POD/008%20LC%20Clerk%20Victoria.pdf accessed 1 March 2022, p 2.

Media Impact

The Guardian – Inside Victoria’s lower house, where non-government business isn’t allowed