The unrelenting rise of management advisory services

July 2023

We recently reported that over the past decade the value of Commonwealth procurements from KPMG, Deloitte, PwC and EY jointly has increased by over 400 per cent, from $282 million in 2012-13 to over $1.4 billion in 2021-22. The vast majority of this is comprised of “management advisory services” contracts, with our analysis of AusTender data revealing that the value of Commonwealth procurements of management advisory services from the big four consultancies has increased in real terms by more than $561 million, or 1276 per cent – up from $44 million in 2012-13 to $605 million in 2021-22. This increase is driven in large part by the Department of Defence, which accounts for between 79.4 per cent and 26.6 per cent of each of the big four’s Commonwealth management advisory service income.

Current procurement disclosure requirements and practices mean that precisely what is purchased with taxpayer dollars is frequently opaque, leaving government unable to assure the public that they are receiving value for money. In addition, the practice of relying on consultants to do the work of the public sector presents challenges from an accountability perspective: as the recent PwC scandal attests, the lack of a direct line of accountability between employees of the big four and government means that holding the former to account for wrongdoing is dependent upon the big four’s preparedness to do so.

Government reliance on the big four also raises questions of integrity. As our recent research found, the big four make substantial political donations to both major parties (though PwC has since committed to ending this practice). Furthermore, significant conflict of interest concerns are raised by lax Commonwealth lobbying regulation – particularly in relation to post-employment separation periods – and the potential for former partners of the big four to hold positions in the public sector at the same time as they are receiving annuities from their former firms.

The Centre for Public Integrity recommends:

- Recentring the APS as the main policy advisory body in government, with resort to external advisors only where there is a demonstrated and acute need for such services

- Imposing a cap on each department’s use of consultants (with exceptions available for circumstances of national emergency)

- Requiring rigorous reporting by departments to Parliament in respect of the use of consultants

- Broadening the application of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and enhancing AusTender disclosure requirements, to facilitate meaningful scrutiny

- Strengthening integrity through appropriate lobbying regulation and closing the revolving door, and preventing former partners of the big four who receive annuities from holding public sector roles.

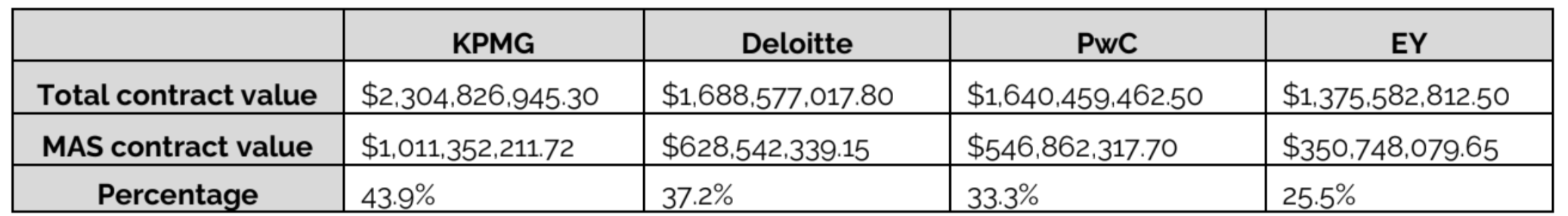

Management advisory services contracts

Management advisory services contracts (‘MAS contracts’) include audit, assurance, project management and strategic services. Our analysis of AusTender data from 2012-13 to 2021-22 for Commonwealth government procurements from KPMG, Deloitte, PwC and EY reveals that these “soft” services make up a large proportion of total contract value for the big four, with each deriving between 43.9 per cent and 25.5 per cent of its government income from MAS contracts (see Figure 1).[1] The significance of management advisory services as compared to the firms’ other services is evident from Figures 2-5.

Figure 1: Percentage of MAS contract value for the big four from 2012/13-2021/22

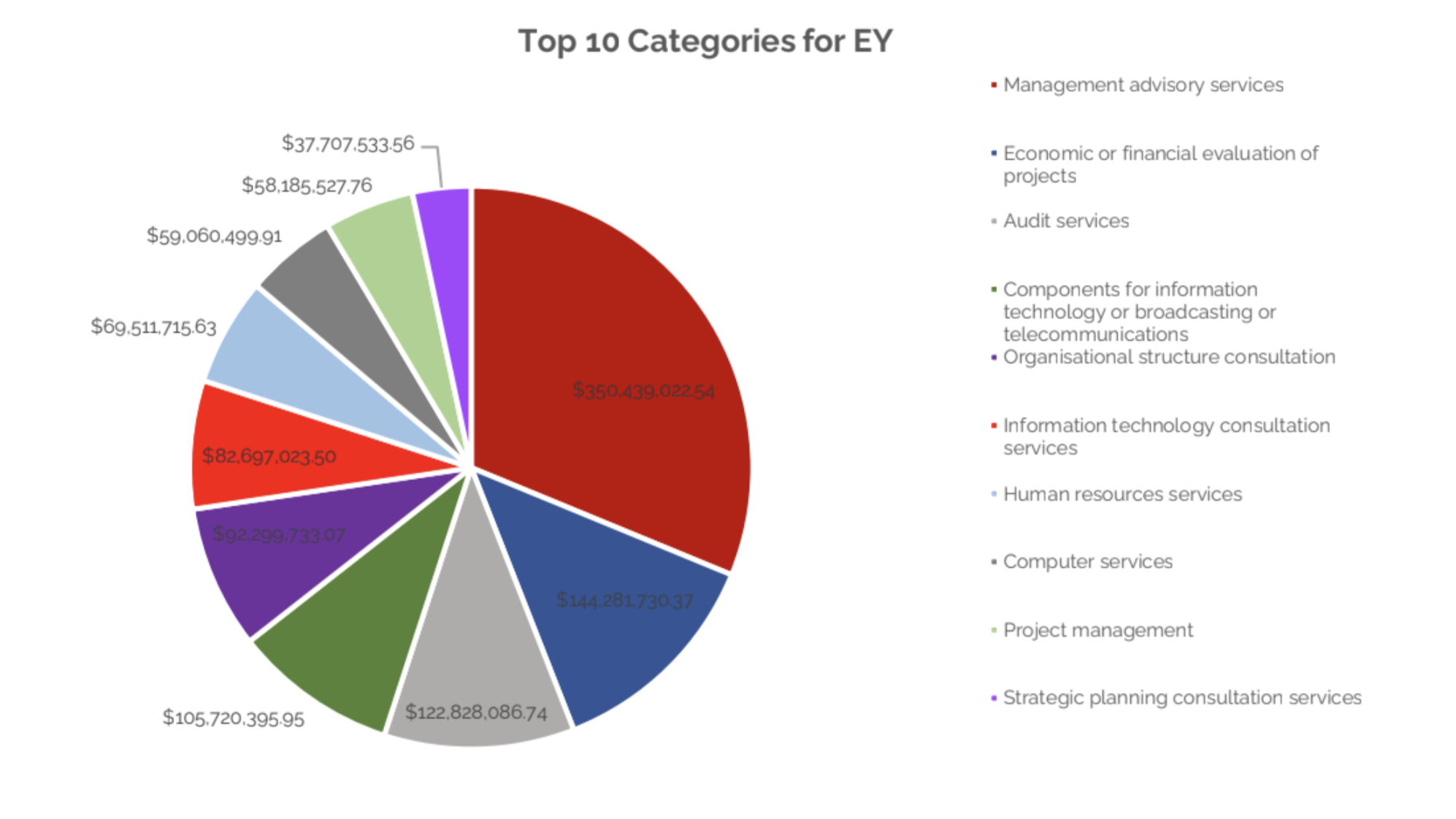

Figure 2: Top 10 procured service categories as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 3: Top 10 procured service categories as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 4: Top 10 procured service categories as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 5: Top 10 procured service categories as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

AusTender does not provide detailed information on the output of management advisory services procurements, with the descriptions accompanying contract disclosure including such unintelligible terms as: ‘Program and Product Management Service and Support’, ‘Project Documentation Suite Services Continuation’, ‘Development Strategy’, ‘Contractor Support’, and ‘Strategic Support Services’.

The service providers offer little more insight into precisely what taxpayer dollars are buying when government procures management advisory services: the KPMG Management Consulting website, for example, states that ‘Our professional advisers can assist both public and private sector organisations understand their most important value drivers and work with them to help achieve tangible and lasting improvements in performance.’[2] The PwC Advisory Services website claims that: ‘Our advisory practice, which comprises Deals and Consulting, is the partner of choice to assist global and local clients and governments to design, manage and execute lasting change, based on trusted relationships, deep industry knowledge and professional experience’.[3]

The dearth of meaningful transparency in respect of procurements costing Australian taxpayers vast sums is deeply concerning.

Increase in management advisory services contracts

Over the past 10 years, the value of management advisory services procured by the Commonwealth from the big four consultancies has increased in real terms by more than $561 million, up from $44,037,781.03 in 2012-13 to $605,798,910.32 in 2021-22. This represents a 1276 per cent increase.

While MAS contract value has been increasing steadily since 2012-13, it increased by more than 100 per cent between 2016-17 and 2017-18 (up from $93,479,535.80 to $195,716,136.66), and again between 2017-18 and 2018-19 (to $394,873,002.99). The likely cause of such substantial increases was the Average Staffing Level (‘ASL’) cap introduced by the Abbott Government in 2015. This cap, which set the level of civilian government sector employees at 167,596, was abolished by the Albanese Government in 2023 on the basis that it had ‘impacted on services provided to Australians, eroded public sector capability, reduced job security and wasted taxpayer funds’.[4]

Figure 6: MAS contract value by firm from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 6: MAS contract value by firm from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 7: Share of MAS contract value by firm from 2012/13-2021/22

Breakdown of management advisory services contracts

Over the period analysed, KPMG received more than $1 billion in taxpayer money for its management advisory services – more than any of its big four counterparts. Deloitte received more than $628 million, PwC more than $546 million and EY more than $93 million.

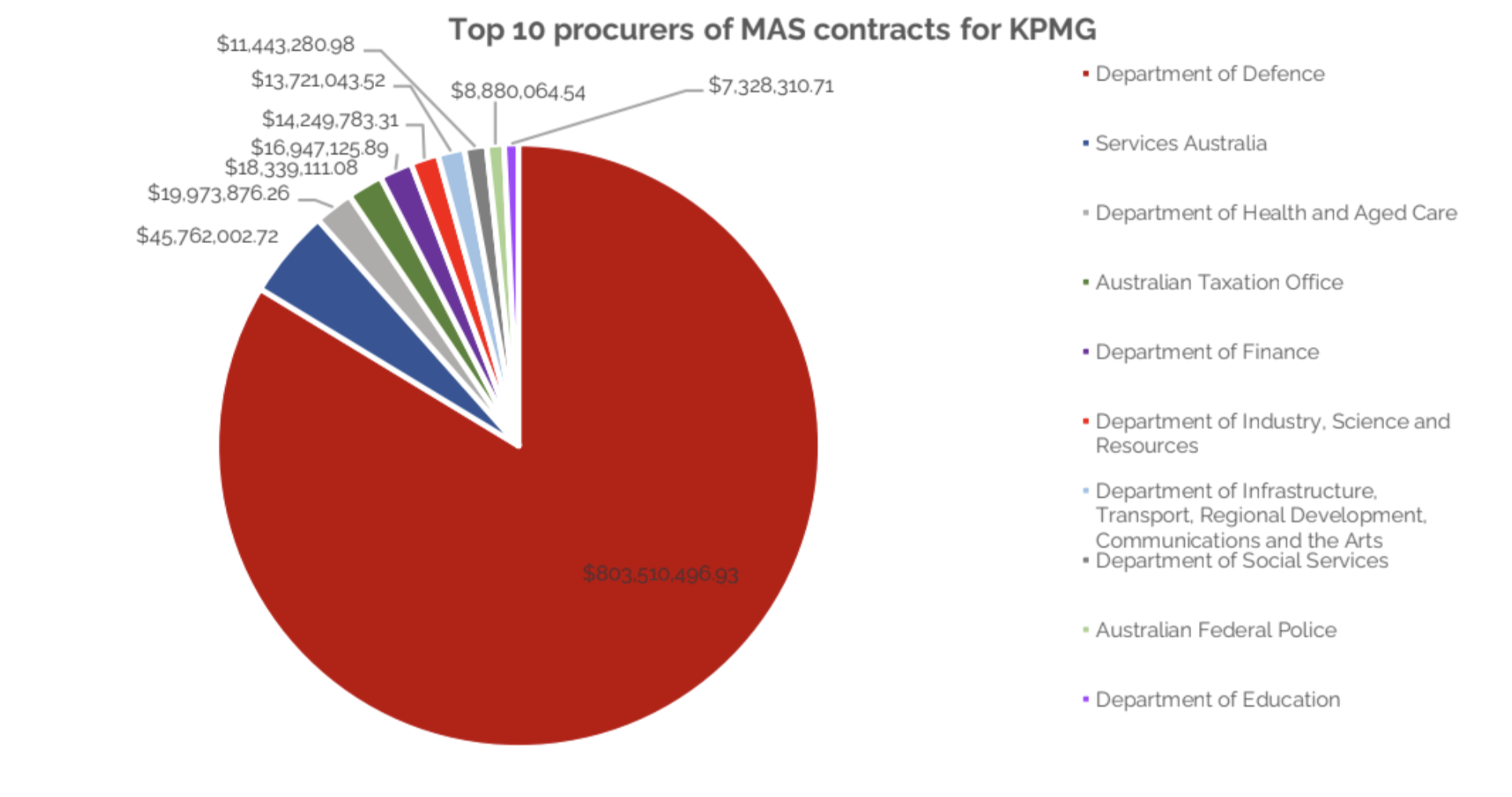

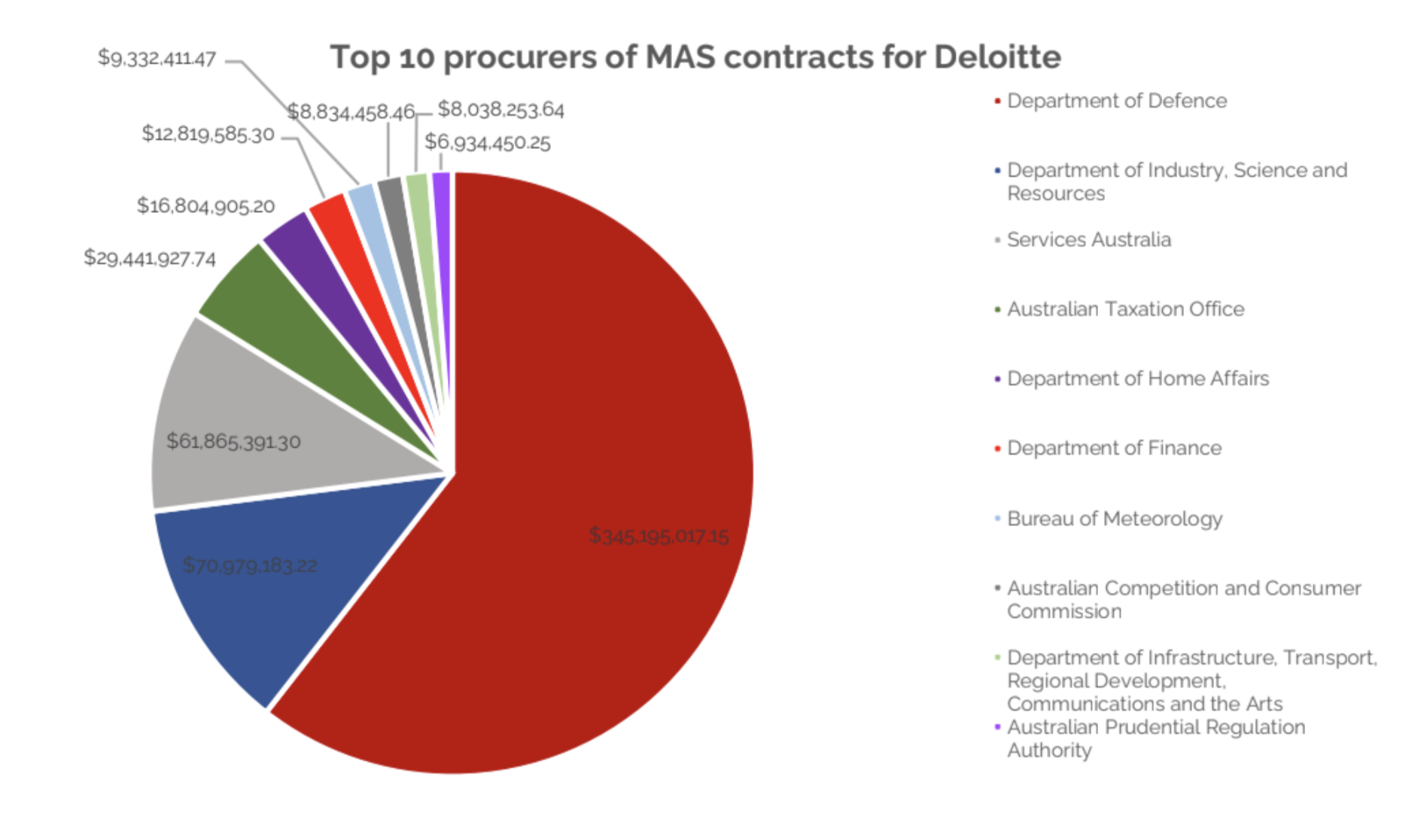

As Figures 8-12 demonstrate, each of the big four derives very substantial income from the Department of Defence for the provision of management advisory services. KPMG is most heavily dependent on Defence: 79.4 per cent of its MAS contracts, worth a total of $803 million, were commissioned by that Department over the period studied. Slightly more than half of Deloitte’s MAS contracts, and 41.8 per cent of PwC’s, come from Defence; only EY derives less than one third of its MAS income from that Department.

Because of the inadequate descriptions accompanying the disclosure of procurements in AusTender, it is very difficult to identify precisely what Defence is procuring when it purchases management advisory services from the big four. A sample includes such descriptions as ‘business support services’, ‘process and resource review’ and ‘logistics service provider’. What is meant by any of these descriptions is unknown.

Figure 8: Value and percentage of firm’s MAS income derived from Defence from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 9: Top 10 procurers of MAS contracts for KPMG as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 10: Top 10 procurers of MAS contracts for Deloitte as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 11: Top 10 procurers of MAS contracts as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 12: Top 10 procurers of MAS contracts for EY as disclosed on AusTender from 2012/13-2021/22

Audit

Audit services procured by government may be categorised in various ways on AusTender: one way in which they may be categorised is as management advisory services.[5] Figures 13-15 demonstrate that audit contributes a negligible percentage of MAS contact value. Out of the big four, KPMG derives the greatest percentage of its MAS contract value from audit (5.7 per cent), while Deloitte derives the smallest (.4 per cent).

Figure 13: Value and percentage of firm’s MAS income derived from audit from 2012/13-2021/22

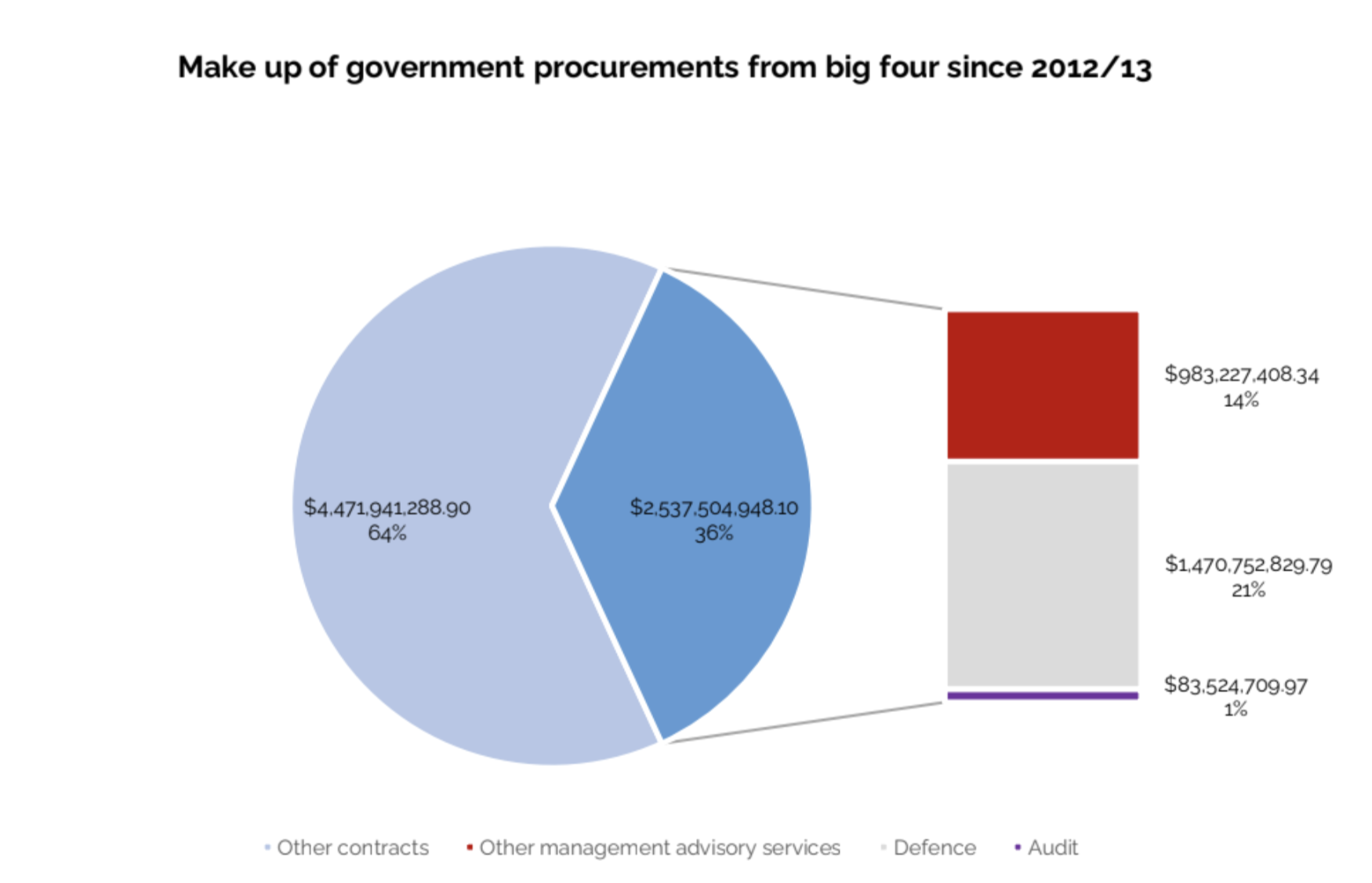

Figure 14: Make up of big four government procurements from 2012/13-2021/22

Figure 15: Make up of firm MAS contract value from 2012/13-2021/22

Accountability

The explosion in the value of MAS contracts presumably reflects an increase in the outsourcing of management and strategy decisions, which must be able to be held accountable. Yet insofar as consultants are external to government, they are exempt from existing government accountability mechanisms. This lack of direct accountability is clearly evident in the recent PwC scandal: had the employees claimed to have breached confidentiality obligations been Commonwealth public servants, they could have been held directly accountable by government, via the Australian Public Service Code of Conduct and their contracts of employment.

Although there is no suggestion that public money is being misspent, the current system of accounting for government procurements gives little detail about precisely what is being purchased. Taxpayers are not given sufficient information to build confidence that they are getting value for money.

Procurement data

The data used to produce this analysis are taken from AusTender, the Australian Government’s central procurement information system. Pursuant to rule 7.18 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which are issued by the Minister for Finance under s105B(1) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (Cth), certain entities are required to report above-threshold contracts and amendments on AusTender within 42 days of entering into them.

Rule 7.19 provides that the reporting threshold for non-corporate Commonwealth entities is $10,000, whereas the reporting threshold for corporate Commonwealth entities prescribed under s 30 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (Cth) is $400,000 (or $7.5 million, in the case of procurements of construction services). Currently, 48 (out of a total of 72) corporate Commonwealth entities are not prescribed for the purposes of the CPRs: this means that they are not required to disclose any information at all under those rules.[6]

As the Foreword to the CPRs acknowledges, ‘[a]chieving value for money […] is critical to ensuring that public resources are used in the most efficient, effective, ethical and economic manner.[7] It is difficult to see how this sentiment is not equally important in respect of all entities procuring goods and services with public funds.

Recommendations

The increased outsourcing of policy work to private contractors who are not directly accountable, financially back both parties and may present conflict of interest challenges raises questions of integrity and public value-for-money. To address these, and arrest the decimation of Australia’s public service, the Centre for Public Integrity recommends:

- Recentring the APS as the main policy advisory body in government, with resort to external advisors only where there is a demonstrated and acute need for such services;

- Imposing a cap on each department’s use of consultants (with exceptions available for circumstances of national emergency);

- Requiring rigorous reporting by departments to Parliament in respect of the use of consultants;

- Broadening the application of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and enhancing AusTender disclosure requirements, to facilitate meaningful scrutiny;

- Strengthening integrity through appropriate lobbying regulation and closing the revolving door, and preventing former partners of the big four who receive annuities from holding public sector roles.

References

[1] All dollar values referred to in this paper are inflation-adjusted 2023 dollars.

[2] KPMG, ‘Management consulting’ https://kpmg.com/au/en/home/services/advisory/management-consulting.html, accessed 19 June 2023.

[3] PwC, ‘Advisory services’, https://www.pwc.com/rw/en/services/advisory-services.html accessed 19 June 2023.

https://www.themandarin.com.au/190453-labor-promises-rebuild-public-service-capability/ accessed 19 June 2023.

[5] For example, some procurements described as relating to audit services are categorised as “Business support services”, “Professional procurement services” and “Audit services” and “Accounting services”.

[6] These include the Cotton Research and Development Corporation, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Wine Australia, Australian Renewable Energy Agency, Clean Energy Finance Corporation, Army and Air Force Canteen Service (Frontline Defence Services), Australian Military Forces Relief Trust Fund, Defence Housing Australia, Royal Australian Air Force Veterans’ Residences Trust Fund, Royal Australian Air Force Welfare Trust Fund, Royal Australian Navy Central Canteens Board, Royal Australian Navy Relief Trust Fund, Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority, Australian National University, Coal Mining Industry (Long Service Leave Funding) Corporation, Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Australian Sports Commission, Food Standards Australia New Zealand, National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority, Airservices Australia, Australia Council, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Australian Film, Television and Radio School, Australian Postal Corporation, Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Infrastructure Australia, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, National Library of Australia, National Transport Commission, Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility, Screen Australia, Special Broadcasting Service Corporation, Anindilyakwa Land Council, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Central Land Council, Indigenous Business Australia, Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation, Northern Land Council, Northern Territory Aboriginal Investment Corporation, Tiwi Land Council, Torres Strait Regional Authority, Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council, Australian Hearing Services (Hearing Australia), National Disability Insurance Agency, Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation, and the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation.

[7] Foreword to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules 9 June 2023 < https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-06/Commonwealth%20Procurement%20Rules%20-%2013%20June%202023.pdf > accessed 1 July 2023.

Media Impact

ABC 730 – An investigation into the billions of taxpayer funds going to the big four consulting firms

The Guardian – Australian government spending on big four consultancy firms up 1,270% in a decade, analysis shows

Mandarin – The Mandarin and Crikey’s ‘revolving door’ list: How power bleeds between politics and the big four

AFR – PwC to ban political donations over tax leaks scandal

The Guardian – Australian government spending on big four consultancy firms up 1,270% in a decade, analysis shows

AFR – Consultant work for federal agencies jumps 1300pc

The New Daily – Calls for royal commission as PwC, Deloitte scandals widen